Strategies for Preventing and Managing Burnout

RELEASE DATE

October 1, 2025

EXPIRATION DATE

October 31, 2027

FACULTY

Katherine Hale, PharmD, BCPS, MFA

Freelance Medical Writer

Richland, Washington

FACULTY DISCLOSURE STATEMENTS

Dr. Hale has no actual or potential conflicts of interest in relation to this activity.

Postgraduate Healthcare Education, LLC does not view the existence of relationships as an implication of bias or that the value of the material is decreased. The content of the activity was planned to be balanced, objective, and scientifically rigorous. Occasionally, authors may express opinions that represent their own viewpoint. Conclusions drawn by participants should be derived from objective analysis of scientific data.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Pharmacy

Pharmacy

Postgraduate Healthcare Education, LLC is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider of continuing pharmacy education.

UAN: 0430-0000-25-105-H01-P

Credits: 2.0 hours (0.20 ceu)

Type of Activity: Knowledge

TARGET AUDIENCE

This accredited activity is targeted to pharmacists. Estimated time to complete this activity is 120 minutes.

Exam processing and other inquiries to:

CE Customer Service: (800) 825-4696 or cecustomerservice@powerpak.com

DISCLAIMER

Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any procedures, medications, or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed or suggested in this activity should not be used by clinicians without evaluation of their patients’ conditions and possible contraindications or dangers in use, review of any applicable manufacturer’s product information, and comparison with recommendations of other authorities.

GOAL

To familiarize participants with the characteristics of burnout and potential strategies and resources available for burnout prevention and management.

OBJECTIVES

After completing this activity, the participant should be able to:

- Define burnout syndrome and the dimensions that characterize burnout.

- List factors that contribute to burnout and methods to assess it.

- Discuss individual and organizational strategies to prevent and manage burnout.

- Identify practical tools and resources that may be used to prevent and manage burnout.

ABSTRACT: Considered an occupational phenomenon resulting from chronic workplace stress, burnout affects many pharmacists and other pharmacy staff across all sectors of practice. Burnout rates as high as 75% have been reported in community pharmacists and as high as 50% or more in hospital and ambulatory care settings and by pharmacy technicians. High workloads, staffing concerns, and a mismatch between job demands and resources contribute to burnout and have led to increased concerns for patient safety and pharmacist and pharmacy staff well-being. Many individualized, organizational, and national strategies have been proposed to prevent and mitigate burnout. Numerous practical tools and resources are available to facilitate burnout prevention and management and promote positive workplace culture and well-being.

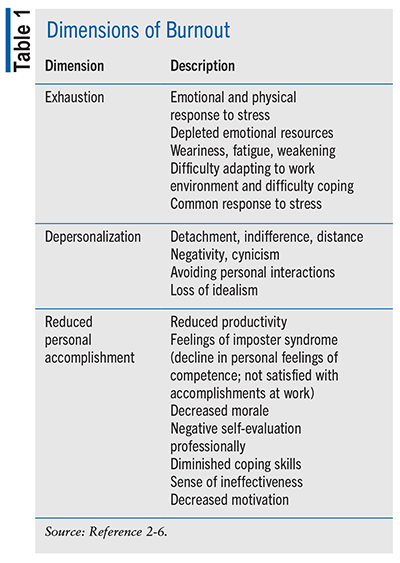

More than 80% of individuals experience some form of stress in the workplace, affecting life outside of work for 50% or more.1 Initially presented and studied as early as the 1970s, burnout has been a focus of research for several decades. Burnout is considered an occupational phenomenon that is occurring in a multitude of professions that are oriented toward serving others (e.g., healthcare, education, and human services) and now non–service-oriented professions as well. Burnout is characterized by three dimensions: exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment (see TABLE 1).2-9

In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) further defined burnout in the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) as an occupational phenomenon (not a medical condition). The WHO defined burnout as “a syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed” with the designated code QD85.5,6 The three dimensions of burnout were further defined as 1) exhaustion/depleted energy; 2) job-related cynicism/negativism and/or increased mental distance; and 3) decreased efficacy.5-8 While burnout and other mental health conditions, such as depression, may occur concomitantly, it should be noted that burnout and depression are not the same. Depression is a medical diagnosis, while burnout is considered a job-related occupational phenomenon.4

Burnout decreases quality of care and worker morale and increases absenteeism and job turnover. Individually, burnout increases personal dysfunction, and relationships suffer. Physical symptoms, such as physical exhaustion, sleep disorders, gastrointestinal symptoms, and changes in eating habits, may occur. Increases in the occurrence of substance use have also been reported.3,9,10

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, a 2019 survey (N = 2,000) indicated that 74% of Americans were concerned about healthcare professional burnout, with 91% indicating that their clinician should employ strategies to avoid burnout. Additionally, 77% indicated that if their clinician was feeling burnout, safety and care would be a concern.11

During the pandemic, high numbers of pharmacists reported at least one dimension of burnout, and rates have remained elevated postpandemic.12,13 Physical exhaustion and emotional exhaustion were reported by 45% and 53% of pharmacists, respectively. Depersonalization (25%), depression/sadness (25%), and anxiety (40%) were also reported.12 In the community pharmacy setting, emotional exhaustion (68.9%), depersonalization (50.4%), and decreased personal accomplishment (30.7%) were reported by pharmacists (N = 411), with 74.9% reporting burnout in at least one dimension overall.14 An additional study of community pharmacists (N = 1,425) found that 67.2% experienced burnout.15 A survey of hospital and health-system pharmacists (N = 380) found that 55.5% were at risk for burnout.16 Reported burnout among ambulatory care pharmacists is as high as 88%, and among pharmacy technicians it as is high as 52%.17,18

A survey of pharmacy residents (N = 163) across 1 year of residency found variable rates of burnout, disengagement, and exhaustion at different survey points. Increased rates occurred in each dimension across 1 year, ranging from 35% to 85% (P <.001). Poor sleep and nutrition and perceptions of not feeling supported by residency program directors may have impacted burnout.19

The cost of burnout in healthcare providers is high. Prepandemic estimated costs of burnout were $4.6 billion, owing to increased turnover and changes in clinical hours. For physicians, turnover related to burnout costs $2.6 billion to $6.3 billion per year as a whole and an estimated $7,600 per physician per year.9,20 Among nursing staff overall, burnout-related turnover costs are much higher at $9 billion yearly.9 While physician and nurse burnout costs have been estimated, the direct and indirect costs of pharmacist burnout in all sectors (community, ambulatory care, hospital, and others) is not clear. Attrition rates are also high. The 2024 National Pharmacist Workforce Survey found that 36.1% and 25.5% of pharmacists would likely/very likely search for new employment or leave their current job within the next year, respectively.21 Physicians (20%) and nurses (40%) have or will have left practice.8

What Drives Burnout?

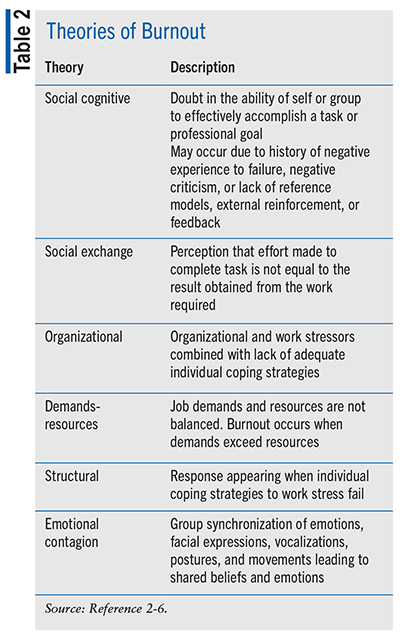

Several explanatory and complementary theories exist describing the why and how of burnout development. These include social cognitive, social exchange, organizational, structural, job demands-resources, and emotional contagion theories (see TABLE 2).2 Self-doubt regarding effectiveness at one’s job is the basis of social cognitive theory, while a perceived mismatch between effort contributed and results obtained is the basis of social exchange theory. Job demands-resources theory is a mismatch between the demands of the job and resources available to complete the work. Failed individual coping strategies in response to workplace stress is the structural theory approach. Organizational theory is considered a combination of lack of adequate individual coping strategies coupled with organizational and work stressors. Emotional contagion theory focuses on shared beliefs and emotions as part of interactions among work groups as part of shared situations and emotions and may affect burnout development at home and at work. Initially proposed as singular theories for burnout development, based on dimensions of burnout syndrome as noted in the WHO definition, many of these theories overlap in burnout cause and development.2-6

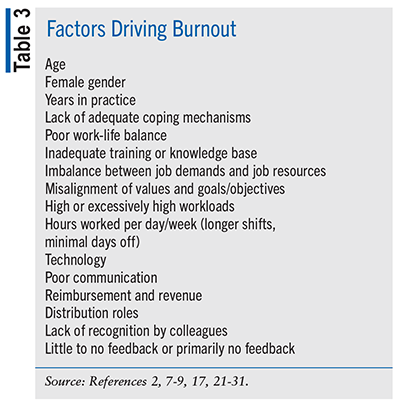

A multitude of factors have been cited to drive burnout and support the above theories (see TABLE 3).2, 7-9 Increased job demands and reduced resources are often primary drivers of burnout. High or excessively high workloads increased from 2014 to 2024 and were highest in chain pharmacies versus independent pharmacies or patient-care–oriented settings.21 In recent years, increased workloads, understaffing, and lack of resources available to complete needed tasks led to pharmacist strikes owing to increased concern for patient safety.22-24 Additional drivers and risk factors for burnout in pharmacists include longer working hours or more hours worked per week, professional advancement (e.g., board certifications), increased nonclinical and administrative tasks, female gender, younger age, less experience, poor work-life balance, distribution roles, lack of burnout-management resources or not knowing how to access or ask for resources, and lack of appreciation by colleagues for professional contributions.17,25-30

Physician satisfaction and drivers of burnout have been linked to obstacles preventing provision of high-quality care, technology and electronic health record challenges, autonomy, organizational leadership, reimbursement, and health reform.31 Many of these factors hold true for pharmacists, regardless of practice location.

In 2008, the Triple Aim was introduced. This aim focused on improving patient-care experiences, population health management, and cost reduction.32 Since its introduction, many changes have occurred systemwide and among the healthcare professions to address and meet these goals and objectives. Demand continues to exceed resources, however, furthering burnout occurrence among healthcare professionals. Therefore, provider well-being has been proposed as a fourth aim.33

Effects of Burnout

Burnout has been linked to reduced patient access and time to complete visits, increased litigation and malpractice claims, increased costs, increased staff and provider turnover, and care-quality reduction.7-9,34-36 Individually, burnout is associated with higher risk of chronic health conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic pain and/or fatigue, gastrointestinal symptoms, sleep disturbances, and occupational injury.7-9,37 Higher rates of depression, anxiety, and substance use have been correlated with burnout in healthcare professionals. Rates of suicide among pharmacists and other healthcare professionals have been shown to be higher than in the general population.7,8,38

Increased risk of medical and medication errors is associated with burnout.7,8,34,35 Globally, when receiving healthcare services, one in 20 patients (5%) may experience medication-related harm. One-half to one-third of medication-related harm is associated with the prescribing/ordering and monitoring/reporting stages of medication use.39 Medication errors are estimated to cost $42 billion annually worldwide.40 Pharmacists may identify up to 70% of errors in the medication-ordering process and reduce medication errors.40 Many factors contribute to medication errors, including lack of training/knowledge, poor communication, language barriers, high/excessive workload, technology, need for protocols/procedures, and interruptions and distractions.41-43

In hospital settings, interruptions and distractions were identified as a primary factor contributing to medication errors, in addition to reduced staff and higher workload.44 Community pharmacists experience seven or more interruptions per hour, ranging from fewer than five to more than 20 times/hour.40,45 In the hospital setting, pharmacists and technicians experience 6.7 and 5.2 interruptions per hour, respectively.46 Interruptions occur every 2 minutes on average and may last up to 100 seconds.47 Nursing studies have shown a 12% increase in risk of error with each interruption.48,49 During the pandemic, concern for having made a medication error was two times that for pharmacists reporting high stress versus lower stress (odds ratio [OR] = 2.08, 95% CI = 1.15-3.74) and similar to that of pharmacists reporting burnout versus no burnout (OR = 1.97, 95% CI = 1.12-3.48).13

Burnout Assessment

Multiple validated instruments are available to assess burnout.50 Several are publicly available, and many are translated into multiple languages.

The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) is perhaps the oldest and most commonly used tool to assess burnout. Multiple iterations and expansions have occurred since the MBI was introduced in 1981. The MBI was developed to assess each of the three burnout dimensions and is considered a standard assessment tool.3,4 The MBI has multiple options available specific to the group assessed (e.g., healthcare personnel, educators). The MBI is a 22-item assessment tool. Items are written in the form of statements specific to personal feelings and attitudes (e.g., “I feel burned out…” or “I don’t really care about…”) and answered based on a seven-point frequency scale.3 The MBI-Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel (MBI-HSS MP) is a modified version of the original MBI that is applicable to healthcare workers.50

Released in 2005, the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) assesses two burnout dimensions, exhaustion and disengagement from work, via three areas of burnout (personal, work-related, and client-related). Nineteen items are answered via a five-point frequency scale.4,50 While no pharmacy-specific burnout assessment tools have been developed, the CBI has been validated to assess pharmacist burnout.51

Released in 2002, the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory is a 16-item survey distinguishing between physical and psychological exhaustion by assessing the two burnout dimensions of exhaustion and work disengagement via a four-point frequency scale.4,50

The Well-Being Index (WBI) is a seven- or nine-item assessment tool that was released in 2010 and designed to focus on multiple dimensions of wellness. These include burnout, fatigue, low mental/physical quality of life, depression, and anxiety/stress. Items are answered via yes/no responses.50 Use of the nine-item WBI was evaluated in a 2019 study of pharmacists (N = 2,231). The mean overall score of the WBI was 3.3 + 2.73, with burnout symptoms present in 59.1% of respondents. Higher WBI scores indicated increased odds of fatigue, burnout, and concern for a major medication error.52

Coping Mechanisms

How individuals respond to stress and burnout is variable. Coping is considered a two-part process that is based on primary appraisal of the event and secondary appraisal of individual coping mechanisms.53 Is the event harmful or threatening? How will the potentially stressful event/situation be managed? Reduced rates of burnout are associated with positive coping strategies, while negative coping strategies have the opposite effect. Positive coping strategies include humor, exercise, spending time with pets/friends/family, job skill improvement, maximizing job resources, and active coping and help seeking.10 Active acceptance is also considered a positive adaptive coping strategy that allows the individual to move on and change his or her emotional reaction to a potentially unchangeable situation.54 Negative coping strategies include avoidance, substance use/abuse, alcohol use/abuse, changes in eating habits (e.g., not eating or binge eating), and social withdrawal.10,53

Positive coping strategies identified by the American Psychological Association in response to workplace stress include55:

- Monitor stressors to identify patterns and reactions

- Implement healthy responses by focusing on good nutrition, minimizing or avoiding alcohol/substance use, practicing good sleep hygiene, incorporating physical activity, and participating in new/ongoing hobbies and activities

- Establish boundaries between work and home

- Rest and recharge by using vacation days or taking any increment of time off where possible, reduce/limit technology use, focus on activities not related to work, and make time to re-energize

- Develop relaxation techniques such as deep breathing, meditation, and mindfulness

- Discuss with supervisor methods to manage workplace challenges and stress to optimize performance

- Develop and use a support system that may include friends, family, employee assistance programs, and/or a psychologist.

Positive and negative self-identified coping mechanisms that have been used by community pharmacists (N = 1,310) include self-care, integrative medicine, personal time, support of family and friends, delegation and time management, substance use, working off the clock (early, late, and on days off), pharmacotherapy, and no coping mechanisms.15

Prevention and Mitigation of Burnout

Methods and strategies to prevent and mitigate burnout may occur at multiple levels, ranging from individual to organizational and national levels.

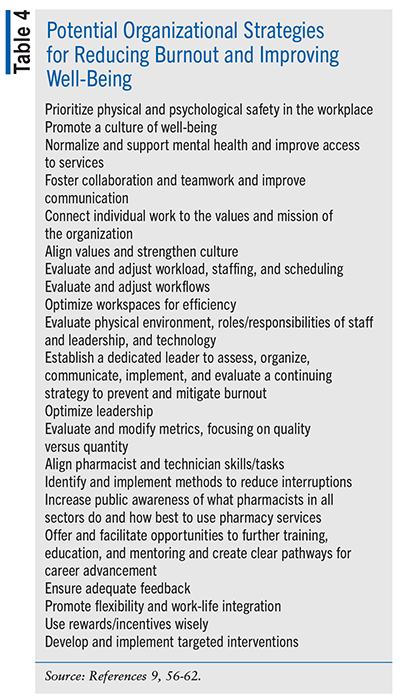

Strategies developed and implemented by organizations have been shown to reduce clinician burnout.7-9,56-58 In 2023, the American Pharmacists Association (APhA), the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), and the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP) convened to establish actionable solutions that organizations, associations, and individuals could implement to improve well-being long-term.59

The summit reconvened in June 2025 (“Implementing Solutions Summit 2.0: Building a Sustainable, Healthy Pharmacy Workforce and Workplace”) to reevaluate and identify new strategies to strengthen the pharmacy workforce and prioritize well-being and mental health.60 At the organizational level, identified actionable solutions included the leverage and expansion of pharmacy technician responsibilities, reimbursement model improvement, address performance metrics, evaluate and modify staffing and scheduling, streamline hiring/onboarding processes, and optimize technology. Additionally, staffing and developing a culture of well-being were suggested by 50.2% and 17.2% of pharmacists (N = 1,425), respectively, when surveyed.15 Although not all-inclusive, TABLE 4 lists additional potential organizational strategies for reducing burnout and increasing well-being.

Promoting a positive work environment is imperative. Environments with strong teamwork, good communication, and positive culture have been found to decrease burnout.9,63 Workplace culture should be evaluated by healthcare organizations and strategies implemented to achieve positive culture, increase employee engagement, and establish a culture of health and value.9 The U.S. Surgeon General advisory recommends building a commitment to the health and safety of health workers into the organization and commit at the highest leadership levels. Regular health and safety assessments and interventions should occur. Development of mental health support services, increased access to quality and confidential mental health care, and community and social connections are recommended. Strategies to reduce bias, discrimination, and health misinformation in the workplace are also recommended.9

Because each organization is unique, a variety of methods may be used to implement burnout prevention and mitigation strategies. Many tools exist, and more will likely be developed in the future.

Individual strategies incorporate more than just self-care. First, it is important to recognize and acknowledge signs of burnout, distress, and mental health concerns when they occur.

Additional strategies include 1) staying connected to family, friends, and coworkers to combat social isolation and loneliness; 2) maintaining good health habits, focusing on nutrition, sleep hygiene, and physical activity; 3) finding moments of joy and prioritizing them; 4) practicing mindfulness; 5) using employee assistance programs; 6) journaling; 7) participating in recreational activities; 8) participating in counseling/therapy; 9) being a voice to advocate for change; and 10) learning new skills and technology.9,63,64

Various strategies that may be employed by national, state, and local associations, insurance companies and payors, and family/friends/coworkers to reduce burnout rates have also been proposed and summarized.6-9,59

Resources and Tools

Commitment to pharmacist, pharmacy personnel, resident, and student well-being and resilience has been affirmed by APhA, ASHP, and the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP).65-67 These commitments are in addition to numerous other organizations that are striving to address provider burnout and promote well-being.68 To increase public awareness of suicide within the pharmacy profession, September 20th was established as Pharmacy Workforce Suicide Awareness Day.69 Additionally, March 18th was established as national Health Workforce Well-Being Day.70

Many practical tools to assist in burnout prevention and management are available in a variety of formats. WellBeing & You (available via ASHP) provides a calculator to estimate the cost of occupational burnout, multiple learning bursts, webinars, podcasts, and resources to assist individuals and organizations in promoting a culture of well-being in the workplace.71

NABP has well-being self-evaluation tools, an anonymous and confidential reporting tool allowing pharmacy personnel to submit positive/negative workplace experiences to help facilitate change, and many other resources available for pharmacy personnel. Courses in mental health first aid, work and fatigue online training, and trauma and healing are also available.72 For residents and student learners, resource guides and toolkits are available from ASHP and AACP to implement well-being, resilience, and burnout-reduction programs.73,74

The National Academy of Medicine has created a compendium of key resources that may be used to facilitate actionable steps to address burnout and well-being.75 The American Medical Association STEPS Forward program was created to provide numerous playbooks, podcasts, webinars, toolkits, success stories, and a program called “The Innovation Academy.” Each is designed to address practice challenges, optimize time management, optimize workflows, enhance patient experiences, improve well-being, and reduce burnout.76

Many non–healthcare-related smartphone apps and computerized applications, books, workshops, and podcasts are also available that promote positive coping strategies and well-being and reduce burnout. Counseling, therapy, and additional medical resources are needed for those with more severe mental health concerns.

Conclusion

The health and well-being of pharmacists, pharmacy personnel, and other healthcare providers remain a focus across all sectors of pharmacy and healthcare. Increasing feelings of being overwhelmed, stress, and burnout continue to threaten the pharmacy workforce, raising the risk for error and reducing care quality. Strategies to mitigate and prevent burnout may be employed not only by individuals and healthcare organizations but by local, regional, and national entities. Many tools are available to facilitate change related to stress and burnout management.

REFERENCES

- U.S. Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Workplace stress–understanding the problem. www.osha.gov/workplace-stress/understanding-the-problem. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- Edú-Valsania S, Laguía A, Moriano JA. Burnout: a review of theory and measurement. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(3):1780.

- Maslach C, Leiter M, Jackson SE. The Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. In: Zalaquett CP, Wood RJ, eds. Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resources. Scarecrow Press, 1997:191-218. www.researchgate.net/publication/277816643_The_Maslach_Burnout_Inventory_Manual. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:103-111.

- World Health Organization. Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon." International Classification of Diseases. 2019. www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- World Health Organization. ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. 2019. QD85: Burn-out. https://icd.who.int/browse/2025-01/mms/en#129180281. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2019.

- National Academy of Medicine. National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2024.

- US Surgeon General. Addressing Health Worker Burnout–The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Thriving Health Workforce. 2022. www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/health-worker-wellbeing-advisory.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- Shahin W, Issa S, Jadooe M, et al. Coping mechanisms used by pharmacists to deal with stress, what is helpful and what is harmful? Exploratory Research in Clinical and Social Pharmacy. 2023;9:100205.

- ASHP News Center. Three quarters of Americans concerned about burnout among healthcare professionals. June 17, 2019. https://news.ashp.org/News/ashp-news/2019/06/17/Clinician-Wellbeing-Survey. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- Bakken BK, Winn AN. Clinician burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic before vaccine administration. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2021;e71-e77.

- Melnyk BM, Hsieh AP, Tan A, et al. The state of health, burnout, healthy behaviors, workplace wellness support, and concerns of medication errors in pharmacists during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Occup Environ Med. 2023;65(8):699-705.

- Patel SK, Kelm MJ, Bush PW, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of burnout in community pharmacists. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2021;61:145-150.

- Cline KM, Mehta B. Burnout and resilience in the community-based pharmacist practitioner. Innov Pharm. 2022;13(4):article 10.

- Kang K, Absher R, Granko RP. Evaluation of burnout among hospital and health-system pharmacists in North Carolina. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2020;77(6):441-448.

- McQuade BM, Keller E, Elmes A, et al. Stratification of burnout in health-system pharmacists during the COVID-19 pandemic: a focus on the ambulatory care pharmacist. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2022;5:942-949.

- Chong JJ, Tan YZ, Chew LST, et al. Burnout and resilience among pharmacy technicians: a Singapore study. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2022;62:86-94.e4.

- Gyori DJ, Ream-Taylor AL, Murphy JA. Evaluation of burnout among pharmacy residents in the United States. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2025;8:533-538.

- Han S, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(11):784-790.

- Mott DA, Bakken BK, Nadi S, et al. Executive summary of the 2024 National Pharmacist Workforce Survey. Pharmacy Workforce Center; Washington, DC: 2024. www.aacp.org/article/national-pharmacist-workforce-studies. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- Kreckel PA. Striking pharmacists put concern for patients first. Drug Topics. April 23, 2024. www.drugtopics.com/view/striking-pharmacists-put-concern-for-patients-first. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- Meara K. CVS pharmacists, staff in Kansas City stage walkout over working conditions. Drug Topics. September 26, 2023. www.drugtopics.com/view/cvs-pharmacists-staff-in-kansas-city-stage-walkout-over-working-conditions. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- Associated Press. CVS responds quickly after pharmacists frustrated with their workload don’t show up. NBC News. September 28, 2023. www.nbcnews.com/business/business-news/cvs-pharmacists-frustrated-workload-dont-show-up-for-work-rcna117821. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- Rech MA, Jones GM, Naseman RW, et al. Premature attrition of clinical pharmacists: call to attention, action, and potential solution. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2022;5:689-696.

- Jones GM, Roe NA, Louden L, Tubbs CR. Factors associated with

burnout among US hospital clinical pharmacy practitioners: results of a nationwide pilot survey. Hosp Pharm. 2017;52(11):742-751. - Dee J, Dhuhaibawi N, Hayden JC. A systematic review and pooled prevalence of burnout in pharmacists. Int J Clin Pharm. 2023;45:1027-1036.

- McQuade BM, Reed BN, DiDomenico RJ, et al. Feeling the burn? A systematic review of burnout in pharmacists. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2020;3:663-675.

- Newsome AS, Smith SE, Jones TW, et al. A survey of critical care pharmacists to patient ratios and practice characteristics in intensive care units. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2020;3:68-74.

- Clements JN, Emmons RP, Anderson SL, et al. Current and future state of quality metrics and performance indicators in comprehensive medication management for ambulatory care pharmacy practice. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2021;4:390-405.

- Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. Rand Health. 2013. www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR400/RR439/RAND_RR439.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759-769.

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-576.

- West CP, Tan AD, Habermann TM, et al. Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA. 2009;302:1294-1300.

- Jones JW, Barge BN, Steffy BD, et al. Stress and medical malpractice: organizational risk assessment and intervention. J Appl Psychol. 1998;73:727-735.

- Hodkinson A, Zhou A, Johnson J, et al. Associations of physician burnout with career engagement and quality of patient care: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2022;378:e070442.

- Marenus MW, Marzec M, Chen W. A scoping review of workplace culture of health measures. Am J Health Promot. 2023; 37:854-873.

- Lee KC, Ye GY, Choflet A, et al. Longitudinal analysis of suicide among pharmacists during 2003-2018. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2022;62:1165-1171.

- World Health Organization. Global burden of preventable medication-related harm in health care: a systematic review. Patient Safety. 2024;1-42.

- Ayanaw M, Lim A, Khera H, et al. How do interruptions and distractions affect pharmacy practice? A scoping review of their impact and interventions in dispensing. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2025;21:667-678.

- Keers RN, Williams SD, Cooke J, Ashcroft DM. Causes of medication administration errors in hospitals: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Drug Saf. 2013;36(11):1045-1067.

- World Health Organization. Medication errors: technical series on safer primary care. Geneva; 2016. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511643. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- Tariq RA, Vashisht R, Sinha A, et al. Medication Dispensing Errors and Prevention. [Updated 2024 Feb 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519065/. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- Aldhwaihi K, Schifano F, Pezzolesi C, Umaru N. A systematic review of the nature of dispensing errors in hospital pharmacies. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2016;5(1):1-10.

- Reddy A, Abebe E, Rivera AJ, et al. Interruptions in community pharmacies: frequency, sources, and mitigation strategies. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2019;15(10):1243-1250.

- Magee K, Fromont M, Ihle E, et al. Direct observational time and motion study of the daily activities of hospital dispensary pharmacists and technicians. J Pharm Pract Res. 2023;53(2):64-72.

- Silver J. Interruptions in the pharmacy: classification, root-cause, and frequency. University of Missouri-Columbia; 2010.

- Beyea SC. Interruptions and Distractions in Health Care: Improved Safety With Mindfulness. PSNet [Internet]. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014.

- Westbrook JI, Woods A, Rob MI, et al. Association of interruptions with an increased risk and severity of medication administration errors. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(8):683-690.

- National Academy of Medicine. Valid and reliable survey instruments to measure burnout, well-being, and other work-related dimensions. https://nam.edu/product/valid-and-reliable-survey-instruments-to-measure-burnout-well-being-and-other-work-related-dimensions/. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- Fadare OO, Andreski M, Witry MJ. Validation of the Copenhagen burnout inventory in pharmacists. Innov Pharm. 2021;12(2):article 4.

- Skrupky LP, West CP, Shanafelt T, et al. Ability of the well-being index to identify pharmacists in distress. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2020;60:906-914.

- McFadden P, Ross J, Moriarty J, et al. The role of coping in the wellbeing and work-related quality of life of UK health and social care workers during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):815.

- Nakamura YM, Orth U. Acceptance as a coping reaction: adaptive or not? Swiss J Psychol. 2005;64:281-292.

- American Psychological Association. (2024, October 22). Coping with stress at work. www.apa.org/topics/healthy-workplaces/work-stress. Accessed September 4, 2025.\

- Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195-205.

- Linzer M, Poplau S, Grossman E, et al. A cluster randomized trial of interventions to improve work conditions and clinician burnout in primary care: results from the Healthy Work Place (HWP) Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1105-1111.

- Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129-146.

- American Pharmacists Association, American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. Implementing solutions: building a sustainable, health pharmacy workforce and workplace. June 2023. https://wellbeing.ashp.org/-/media/wellbeing/docs/Implementing-Solutions-Report-2023.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- ASHP News Center. Pharmacy organizations collaborate to prioritize pharmacy workforce well-being and mental health. July 8, 2025. https://news.ashp.org/News/ashp-news/2025/07/08/pharmacy-organizations-collaborate-to-prioritize-pharmacy-workforce-well-being-and-mental-health. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- Hardeman S, Musselman M, Weightman S, et al. A call to action: how pharmacy leadership can manage burnout and resilience. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2024;81(22):1092-1095.

- Newlon JL, Clabaugh M, Illingsworth Plake KS. Policy solutions to address community pharmacy working conditions. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2021; 61:450-461.

- CDC. Workplace health promotion website. http://cdc.gov/workplace-health-promotion/php/index.html. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- National Academy of Sciences Clinician Well-Being Hub. Individual strategies to promote well-being. https://nam.edu/clinicianwellbeing/solutions/individual-strategies/. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP statement on commitment to clinician well-being and resilience. https://wellbeing.ashp.org/ashps-commitment-to-well-being. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- American Pharmacists Association. APhA statement on commitment to the well-being and resiliency of pharmacists and pharmacy personnel. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/American-Pharmacists-Association_Commitment-Statement.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. AACP statement on commitment to clinician well-being and resilience. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/AACP_American-Association-of-Colleges-of-Pharmacy-Committment-Statement-2021.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- National Academy of Medicine. Organizational commitment statements. https://nam.edu/our-work/programs/clinician-resilience-and-well-being/commitment-statements-on-clinician-well-being/. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Pharmacy Workforce Suicide Awareness Day. https://wellbeing.ashp.org/suicide-awareness-day. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- National Academy of Medicine. Health workforce well-being day. https://nam.edu/our-work/programs/clinician-resilience-and-well-being/health-workforce-well-being-day/. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. WellBeing & you. 2025. https://wellbeing.ashp.org/. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. Mental health and well-being: for pharmacy staff. https://nabp.pharmacy/initiatives/pharmacy-practice-safety/mental-health-and-well-being-resources/. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP resource guide for well-being and resilience in residency training. March 2023. www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/professional-development/residencies/docs/ASHP-Well-Being-Resilience-Residency-Resource-Guide-2023.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Creating a culture of well-being: a resource guide for colleges and schools of pharmacy. www.aacp.org/sites/default/files/2022-08/creating-a-culture-well-being-guide.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- National Academy of Medicine. Compendium of key resources for improving clinician well-being. https://nam.edu/product/compendium-of-key-resources-for-improving-clinician-well-being/. Accessed September 4, 2025.

- American Medical Association. AMA STEPS forward: transform your practice. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/. Accessed September 4, 2025.

The content contained in this article is for informational purposes only. The content is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk.